The Life of George Henry Chambers (1867-1923)

This account is a tribute to my great grandfather, an ordinary man whose life story resonates with the experiences of many who lived during his time, the tail-end of the Victorian era when the accomplishments of Britain were seen through the lens of its vast military. Though I never had the chance to meet him personally, I have come to know him through the memories and stories passed down by his children, painting a picture of a hard-working and dedicated individual.

His time in the military demanded courage, discipline, and a commitment to duty, but he never appeared to allow the harsh realities of war to harden his heart. Instead, by all accounts, he maintained a strong moral compass and an inherent gentle nature. His influence has not only lived on in his children but also in his grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The motivation behind writing this biography is simple: to preserve and share the life of my great grandfather, ensuring that his story continues to be told and appreciated by our family and beyond.

To create an accurate portrayal of his life, I have consulted a range of sources, including public records, contemporary newspapers, and, most importantly, the recollections of his children. These sources have provided valuable insights into his character, challenges, and accomplishments.

– ID, March 2023

Early Life

George Chambers was born in the parish of Wilby in Suffolk, on 2nd February, 1867. He was the fourth of eight children of farm worker William Chambers and his wife Rebecca Brooks.

Wilby is situated six miles east of Eye, 1¼ miles south of Stradbroke in the northern part of Suffolk. At that time it supported a population of 560 people in 126 houses1, almost all exclusively employed in agriculture. George’s father, William, had been born in 1833 in the parish of Fressingfield, some five miles to the north. The Chambers family had been resident in Fressingfield for over 150 years but William had moved to Withersdale, a smaller neighbouring parish to the north, where in 18512 he was working as a farm labourer at Kett’s Farm for Hannah Gowring, a farmer of of 83 acres. Just a couple of miles west was Mendham, where he met and married Rebecca Brooks in 1860. At the time of their marriage, Rebecca was five months pregnant with their first daughter Anna Maria. The couple seem to have fallen out of favour with the local priest as they married in the Hoxne register office instead of the local church and Anna Maria was baptised privately, probably at their home. They lived next door to Rebecca’s parents, both of whom were destitute at that time.3 Her father was sick with consumption and was unable to work. He died in May 1861 aged just forty three.4

By 1863 William and Rebecca’s small family had relocated 20 miles west to the parish of Walsham le Willows where William found employment as a horseman on Blossoms Farm5. George’s two other elder siblings were born here – Rebecca in 1863 and William in 1865. However by the time of George’s birth in 1867 the family were living in Wilby and, with the arrival in 1869 of a new curate, the Rev. Henry S. Marriot, they renewed their relationship with the church. William and Rebecca baptised their four children Anna Maria, Rebecca, William and George on the 4th April 1869. Anna Maria was baptised under the name of Hannah.

The family remained in Wilby for over a decade having four more children: John in 1869, Helen in 1874, James in 1876 and Robert in 1880. Another boy named James had been born in December 1872 but survived only a few months. The family remained in Wilby for over a decade until the sudden and unexpected deaths of both William and Rebecca, a shock which left their family of young children orphaned and subsequently scattered across the country.

Death of Parents

As was common in Suffolk at that time, George’s father, William, had been employed throughout his life as an agricultural labourer and it was in the course of his work that tragedy struck. On Saturday 30th August 1879, while in charge of a wagon and four horses, he fell and his leg was crushed under the wheels of the cart. His leg was so badly broken that the surgeon decided that the only course of action was to attempt an amputation. Two days later tetanus set in and on Tuesday 2nd September, William died. The East Anglian Daily Times reported the inquest the following week:

WILBY. FATAL ACCIDENT - On Thursday evening Mr C W Chaston held an inquest at the Swan Inn, relative to the death of William Chambers, 40 years of age. Maria Mutimer, wife of Charles Mutimer, labourer, deposed that between 1 and 2 o’clock on the 30th August, she saw the deceased in charge of three or four horses and a waggon. He was sitting upon the seat. A few minutes afterwards she saw him crawling away from the waggon to the side of the road; the horses were stopped. Witness at once went to him. She thought he was in the act of getting out of the wagon when he fell down, and the wheels of the waggon went over him. Witness believed he was quite sober. - Mr C G Read, surgeon, Stradbroke, said he attended the deceased on the 30th August for severe fracture of the right leg. With assistance he amputated the limb, but on September 1st lock-jaw set in, which was the immediate cause of death. - The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence.6

His death certificate recorded the cause of death as:

Lock jaw, occasioned by a compound fracture of the right leg caused by the wheels of waggon passing over him on 30th August last, he having accidentally fallen from his waggon on in the road. 7

He was buried the next week on 7th September in Wilby Parish Church. Later on, this dramatic event would be described by George to his son William as his father dying while “stopping a runaway horse”8.

Rebecca was left alone with a family of eight children the youngest of whom, Robert, was just a few months old. George was twelve at this time. Anna Maria, the eldest at 19, was unmarried and five months pregnant. She gave birth to William Robert Chambers on 25th December 1879 in the Union Work House in Eye. It is probable that the entire family had been admitted to the work house by that time.

By April 1881 though, the family were once again living in The Street, Wilby, close by the Swan Inn. None of them were shown as being employed although at 22 and 18 it is likely that Anna Maria and Rebecca were working as servants for local residents. Anna Maria’s son William was living with her, just a short distance from her future husband, and recent widower, Robert Johnson.

However just four months later George’s mother, Rebecca, died of Pthisis, an old name for tuberculosis9. She was buried on 28th August 1881 leaving her eight children as orphans.

This time was remembered as an unhappy, bleak experience by the children as they were swept up by the austere state institutions in place at the time. George recalled that he had lived in an orphanage which he hated and from which he had run away to join the army10

His brother John’s daughter, Jane Ann, was told that he had been in a home when he was young11.

By the 1891 census the family were no longer together. Robert, the youngest, can be found alone aged 11 in the Ling school, part of the Hartismere Union Work House in Eye12. Rebecca had married George Warne of Wingfield in 1882 while Anna Maria had married Robert Johnson in 1885 and remained in Wilby.

George’s elder brother, William, was working as a farm servant at Green Farm in Redlingfield13 and their brother James, 15, similarly employed at Flemings Hall in Bedingfield14, five miles from Wilby. James was later to emigrate to Canada.

John, aged 22, had left Suffolk entirely and was in Great Driffield, Yorkshire a farm servant to Robert Wood15.

Helen, now 17, was in Diss, working as a domestic servant to Robert Chenery a coal merchant and farmer16. A few years later she married Henry Pickett in London17 and perhaps it is an indication of the trauma of being orphaned at age seven that she gave her father’s name as George, not William18.

However, even though the family had been dispersed, they remained in contact with one another. George’s son William recalled seeing papers and letters from James and John and made visits to Helen’s family, the Picketts, in London19.

Army Service

Over Christmas 1887, at the age of 20, George had enlisted in the Royal Artillery. He attested before a magistrate, Rev. R. G. Gorton, at Badingham on 23rd December then underwent a civil medical examination a couple of miles away at Framlingham. This was followed by another examination in Ipswich the next day where he was passed as fit for service. 20

The medical examiner recorded his age as 20 years and 10 months. He stood 5’ 5½" tall, fairly typical for a recruits at that time, with a dark complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. He weighed 10st 6lbs and his chest measurement was 35½". He had a letter G tattooed on his left forearm and a large mole on his left loin. His religion was given as Church of England.21

In Colchester on 26th December, 1887 he signed-up for the Field Artillery for 12 years as a gunner, number RA 65249. The Gladstone government had recently passed the Army Enlistment Act, reducing the service period from 21 years to 12, with the first half spent on active duty and the rest in the reserves.

As a gunner, George was the lowest rank in the artillery and equivalent to a private in the infantry. He would spend the first three months in basic training, learning discipline, building up physical fitness and drilling to learn fundamental military skills. He spent some of his time at the School of Gunnery in Lydd, Kent22. The Field Artillery was organized into four brigades, each with several service batteries and a depot where new recruits would be assigned. George, having signed up in Colchester, was assigned to the 2nd Brigade and became part of the depot battery stationed there until he could be transferred to a service battery.

A field battery was made up of 171 soldiers and 131 horses, and was divided into three sections, each equipped with two 12-pounder breach-loaded artillery guns23. These guns were capable of firing shrapnel rounds and had a range of 5000 yards, making them a powerful force on the battlefield. The guns were towed by a total of six horses, allowing the battery to be highly mobile and adapt to changing circumstances. Ammunition was transported in nine artillery wagons and twelve small arms wagons, along with three transport wagons.

As a new recruit, George would have played an important role in the battery by maintaining the equipment, wagons, and horses. With his agricultural background, he was well-equipped for the job.

Posting to India

In 1888, on 25 September, George was posted to India, forming part of the annual relief for troops already in service24. 162 men of the 2nd Brigade were drafted from Colchester depot and put under the command of Lieutenant S. G. Chamier for the journey. They were joined by 38 men drafted from the Garrison Artillery depot at Great Yarmouth.25

The Evening Star of Ipswich reported their departure:

The men, who appeared in capital health and spirits, fell in on the Barrack Square about 6:30am – not one being missing – and amused themselves with singing “Auld Lang Syne,” and cheering for popular officers and sergeants, until the word was given to march, when they tramped sturdily to St. Botolph’s Station, preceded by the Band, and greeted by hearty farewells and good wishes from the townspeople and their comrades at the Camp. The entrainment was effected rapidly and in excellent order, and a quarter to eight the “special” steamed out of the station, the band playing the usual farewell airs, and the gallant gunners cheering lustily.26

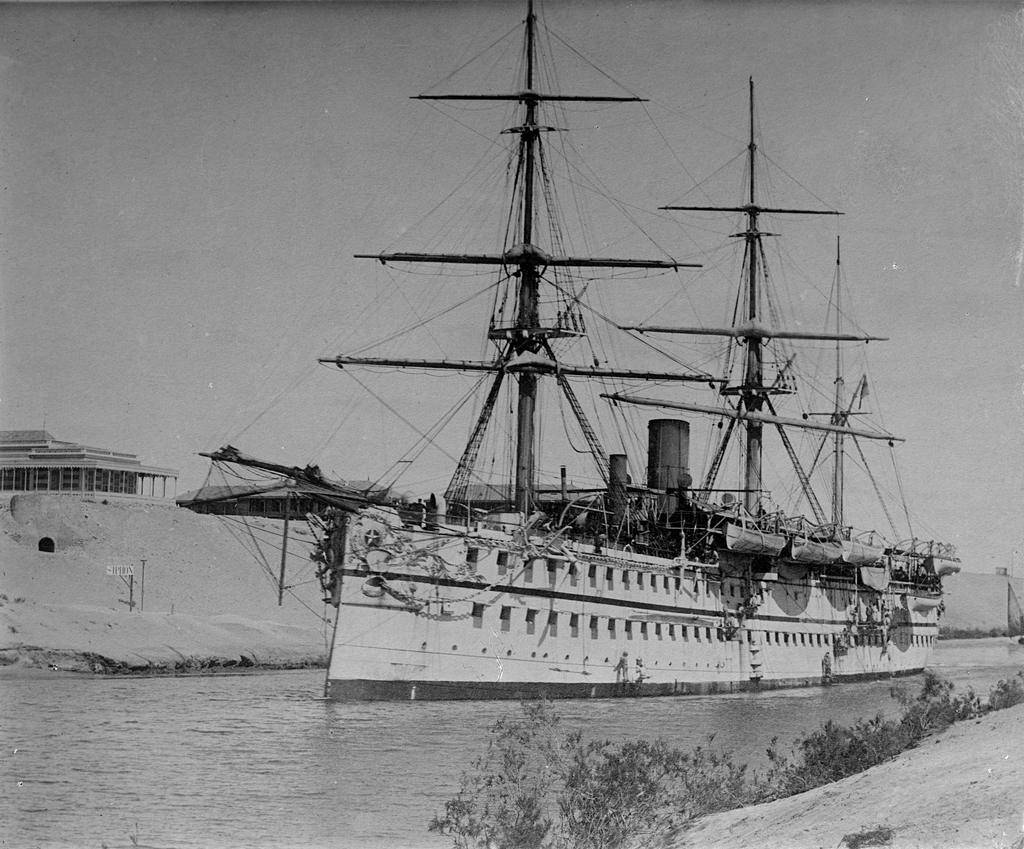

HMS Malabar, Suez.

The draft from the depot departed from Portsmouth on 26th September via the HMS Malabar, a troopship designed to ferry troops between England and British India27. They were joined by four further Field Artillery batteries, one Horse Artillery battery and several hundred new artillery recruits drafted from across the county. In all, 1238 men, 57 women and 73 children were aboard.28 Captained by Arthur Dalrymple Fanshawe, the journey was to take a little under a month, calling at Queenstown (now Cobh in Ireland), Malta, Port Said and Suez, eventually arriving in Bombay on the 24th October, 188829. The troops disembarked at Sassoon dock the next day and departed by special trains to transit camps in Deolali. to the north-east, and Pune, to the south-east, both about 100 miles from Bombay.

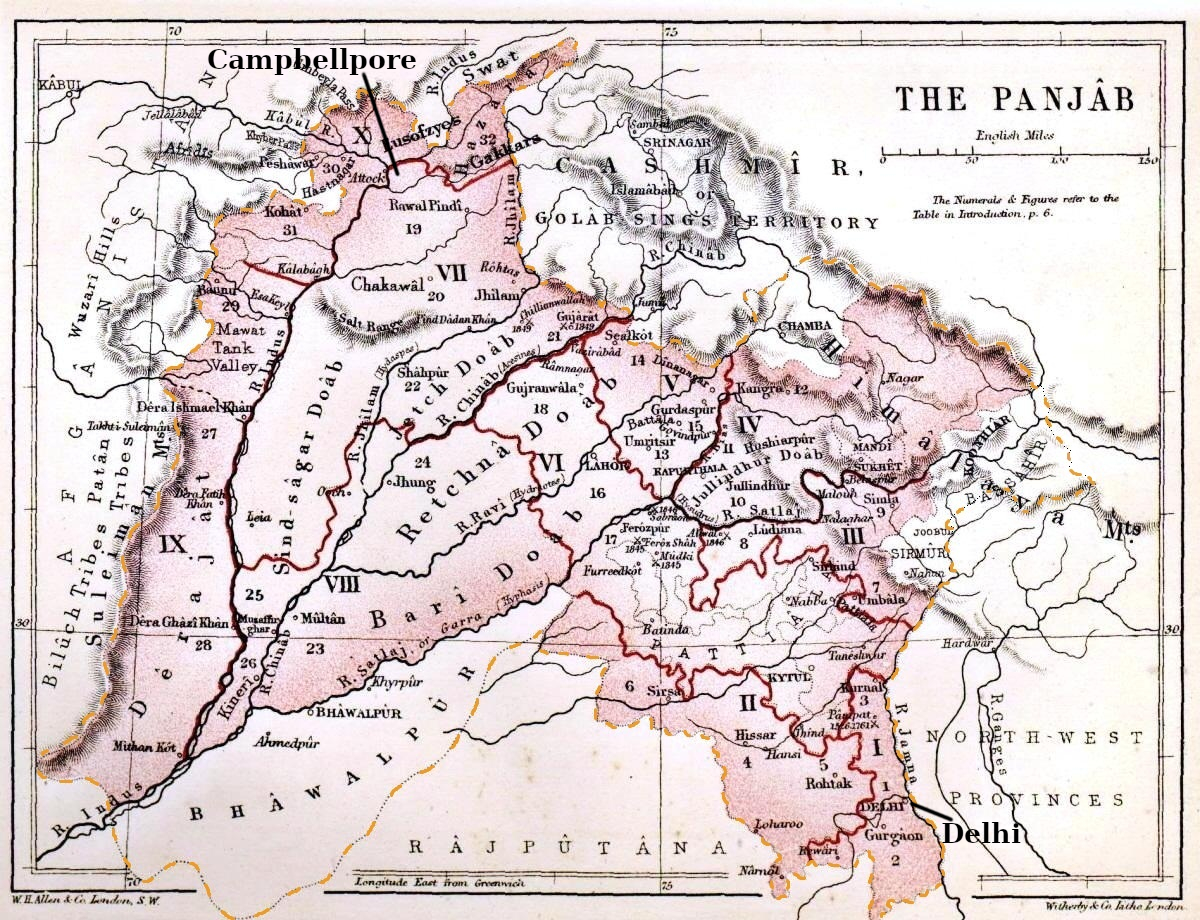

George was to be assigned to the 2nd Brigade’s J Battery in Campbellpore on the North-Western Frontier. He would have first travelled to Deolali camp to acclimatise, probably spending several weeks carrying out route marches and close order drill30. The soldiers nicknamed the camp “Doolally”, which became a slang term for temporary derangement, due to its association with “Deolali Tap”, or “camp fever”31.

Campbellpore, a permanent military station near the present-day city of Attock in Pakistan, was situated on the banks of the Indus River in the north-west of India. It was one of the northernmost points in the province of Punjab and a symbol of British control in the region. The British had recently subdued local warring clans and were focused on development, building the first permanent bridge over the Indus and introducing rail transport to the area. In the years preceding George’s arrival, the Punjab administration had begun an extensive plan to irrigate the previously barren wastelands and win local favour through the construction of a series of canals.

Map of north-west India, late 19C.

2nd Brigade J Battery had been stationed at Campbellpore since August of the previous year, after having spent three years in Rawalpindi (near present-day Islamabad), the most important military station in India. At Campbellpore, J Battery joined the 5th Division, 1st Battery of heavy Garrison Artillery who had held the station since their arrival in India in 1884.

Campbellpore lay over 1100 miles from Deolali Camp and George may have travelled by train for at least some of this distance and marched the rest, arriving early in 1889. He was stationed at Campbellpore for about nine months. In June 1889, J Battery received orders to relocate from Campbellpore to Saugor in central India by route march32 the following cold season.33 The 1st heavy artillery battery were to go to Jhansi.

The next month, the Royal Artillery underwent a wide reorganisation. The field artillery brigades were amalgamated into eighty numbered batteries while the garrison artillery were grouped into three geographic districts. George’s unit, the 2nd Brigade J Battery, became the 78th Battery Field Artillery, while the 5th Division, 1st Battery became the Eastern Division 23rd Battery of Garrison Artillery.

On 25th September both batteries set off on the 550 mile march to Camp Gurgaon, a new artillery practice camp, 20 miles south of Delhi. A notice in the Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) placed by the commanding officer of the 23rd battery on 24th September 1889 included their route in detail should any letters need to be sent to the troops34:

Hasn Abdal 26th September Jullundur 25th October

Rawalpindi 29th … " … Philour 28th … " …

Goojar Kjan 2nd October Kuna-ki-Serai 31st … " …

Jhelum 6th … " … Umballa 5th November

Lalla Moosa 8th … " … Peeplee 7th … " …

Wazeerabad 10th … " … Karnal 9th … " …

Gujranwalla 13th … " … Panee Put 12th … " …

Moreedkee 15th … " … Sursowlee 14th … " …

Lahore 17th … " … Delhi 18th … " …

Amritsar 20th … " … Gurgaon 20th … " …

Jundeealah 21st … " …

A correspondent for the Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) reported the passage of the 78th battery through Jhelum:

The following batteries passed through Jhelum the other day en route to Lahore :- No. 78 Battery, Royal Artillery; No. 23 Battery Royal Artillery; No. 23 Battery sent their guns to Kharian by rail as ferry boats at Jhelum were deemed too impractical to convey them on board across the river. A crowd of natives assembled at the river to see the gunners handling their guns and the elephants crossing the river. I hear that both these batteries come from Campbellpore.35

The heavy artillery battery’s 40-pounders weighed five times the 12-pounders used by the field artillery and, in India, were drawn by two elephants hitched one before the other.

The units made good time on their march, taking 57 days, and arrived at Gurgaon (now Gurugram, twenty miles to the south of New Delhi) on the 21st November. Camp Gurgaon was the largest of its kind in India with eight artillery batteries present for three weeks of practice: two Horse, four Field and two Garrison. On the 11th December the assembled troops were observed and addressed by the Commander-in-Chief of India, Sir Frederick Roberts, who was conducting a country-wide tour of the British Army36.

On 13th December the camp broke up and the batteries proceeded to their assigned stations. Saugor lay a further 370 miles march to the south-east and the 78th Battery probably arrived mid January 1890.

Saugor (now known as Sagar) lay on the high plains of central India, close to the lake of the same name. The town was guarded by a fort, which had been built a century prior to the arrival of the British. The fort consisted of twenty round towers, varying from twenty to forty feet high, connected by thick curtain walls enclosing over 6 acres. The British had added a magazine, a large medical supply store and a barrack. During the 1857 rebellion, the town had been under siege for 9 months, after which it was kept constantly garrisoned with a regiment of infantry, two artillery batteries supplemented by a native regiment of cavalry and one of infantry.

Return To Europe

George was stationed in Saugor until September 189137. During this time, he studied for and acquired a Third-class Certificate of Education38. This certificate was a requirement for promotion to the rank of Corporal in the infantry or Bombadier in the artillery. To receive the certificate, George had to demonstrate his ability to read aloud, write from dictation, and perform arithmetic calculations involving the four compound rules and monetary reduction. A higher level of proficiency, represented by a Second-class Certificate, was necessary for promotion to Sergeant. This certificate required more advanced writing and dictation skills, as well as a deep understanding of regimental accounting and the ability to handle mathematical concepts such as proportions, interest, fractions, and averages.

The Battery had received orders to return to Britain and were to spend the next two months marching the 500 miles to Bombay. On 4th November 78th Battery embarked on the HMS Crocodile, the sister ship of the Malabar, marking the end of just over three years of service in India for George. They arrived in Portsmouth on 30th November, 1891 and the 78th Battery proceeded to take up quarters in Athlone in Ireland.39

Two years later, George had once again been studying for promotion and, in September 1893, passed the Wheeler’s course at Woolwich, the headquarters of the Royal Artillery. A Field Artillery battery required four wheelers to maintain the gun carriages. That summer the 78th battery had been drilling at the Curragh40 in County Kildare, near Newbridge where George’s son William would be born twelve years later. George must have had leave to travel from Ireland to London to take the examination. At the end of October, after the training season, the battery returned to Athlone41.

The next year, on 4th October, 1894 he extended his service to 12 years and was promoted to bombadier wheeler on the 18th. The following day he was transferred to the 4th Battery, Mountain Artillery, stationed at that time at Newport Barracks in Monmouthshire. It was in Newport that George was to meet and marry Louisa Hemmings.

Ten batteries of the Garrison Artillery were designated Mountain Artillery. Nine of the batteries were stationed in India and one, the 4th, was stationed at the division’s depot in Newport. The batteries were specialists in traversing mountainous terrain to attain advantageous positions in wartime. Unlike other artillery units that utilized horses, the Mountain Artillery employed mules to transport their artillery, given the rugged and challenging terrain they faced.

The use of mules had its limitations, as each mule could only carry a load of around 200 pounds. As a result, the artillery guns used by the Mountain Artillery were smaller, with a 2.5-inch calibre, and were designed to be divided into two pieces for ease of transportation. In the field, the gun could be assembled in under 20 seconds. Five mules were needed to carry each gun: one for the axle, two for the iron-rimmed wooden wheels and two for the two pieces of the gun.

To sustain their operations, a Mountain Artillery battery required not only the thirty mules needed to transport their six guns, but also an additional thirty for carrying ammunition, thirty for spare parts, tools, and a forge for the farrier, thirty for relieving the gun mules on long marches, and sixty-five for carrying rations, water, and baggage.

The subject of the Kipling Poem, Screw-Guns, published in 1890 is the mountain artillery, sung from the point of view of a gunner. It became popular among the soldiers and eventually it became the unofficial song of the Royal Garrison Artillery, often sung after dinner at regimental dinner-nights.

Marriage to Louisa

Louisa Hemmings was born on 2nd August, 1876 near Risca, a town located five miles from Newport along the Ebbw River. Her father, Joseph Ximanes (Jimenez or Himenes), was an immigrant from the Americas who later adopted the anglicized name of Hemmings42.

Her mother, Bridget, was a member of a large Irish immigrant family and, tragically, she had suffered the loss of three husbands. Her third, Louisa’s father, had been killed in 1880 in a huge coal mine explosion at the Black Vein colliery in Risca where he had worked as a labourer. She had since married John Jones, a coal miner.

Louisa was probably working as a servant at the time she and George met. Some years earlier she had been working as a general servant in Christchurch, a mile or two to the east of Newport43. Louisa’s brother Frank had enlisted in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in 1894 who were then also stationed at Newport so he may have introduced George to his sister. Frank was due to be posted to India in July so perhaps he sought out and befriended fellow soldiers like George who had experience of life there.

It is also possible the couple may have originally met at one of the social events organised by the officers at the barracks. Their son, William, later recalled that George and Louisa were accomplished dancers and they used to give the lead at army functions.44 The South Wales Weekly Argus and Monmouthshire Advertiser reported one dance on 3 February, 1894:

On Friday evening the non-commissioned officers of the detachment of Royal Artillery stationed at Newport Barracks gave a dance, in continuation of the event instituted as an annual affair by their predecessors. In addition to those in barracks many Volunteer soldiers and civilian friends were invited to the gathering, and despite the unpropitious state of the weather there was a large attendance, the barracks recreation-room, in fact, in which the dance was held, being at times inadequate for the couples who stood up to do “the light fantastic.”45

They were married on 23rd December, 1895 at the Register Office in Newport. The couple had to resort to this option due to their differing religious affiliations: Louisa’s family were firmly Roman Catholic but George had been baptised into the Church of England. At the time, a Catholic and a Protestant could not marry in the Catholic Church unless they had already married by civil or Protestant ceremony. Moreover, any attempt to solely perform the marriage through Catholic rituals was considered null and void.

Around this time George adopted a second name – Henry. Prior to his marriage all records show his name simply as George, but past this point he refers to himself as George Henry. It is possible that he converted to Roman Catholicism and took Henry as his confirmation name, but if so why did he and Louisa choose to marry at the Register Office instead of St. Mary’s Church in Newport?

Both George and Louisa misstated their age, presumably to reduce the apparent age difference from nine and a half years to five. George claimed to be twenty-six but was just a few months short of twenty-nine, whereas Louisa stated she was twenty-one but was actually just over nineteen. George also claimed his father was a master wheelwright, although by every other account, William was a horseman or farm labourer.

Three members of Louisa’s extended family witnessed the wedding: her cousins Edward and Margaret Mansell and Alfred Harvey, the husband of her half-sister Jane (also known as Jenny). It is perhaps surprising that there were no witnesses connected with George, such as a fellow gunner. The marriage was recorded in George’s official army record by Major Fulton, commander of the 4th Mountain Battery.

The number of married soldiers per regiment was limited. No soldier could marry without the permission of their commanding officer and then only if he was of good character, had served for at least seven years and had savings set aside. Those who married with permission were said to be on the strength of the army. Married soldiers lived with their wives and children in an area of the barracks set aside for families.

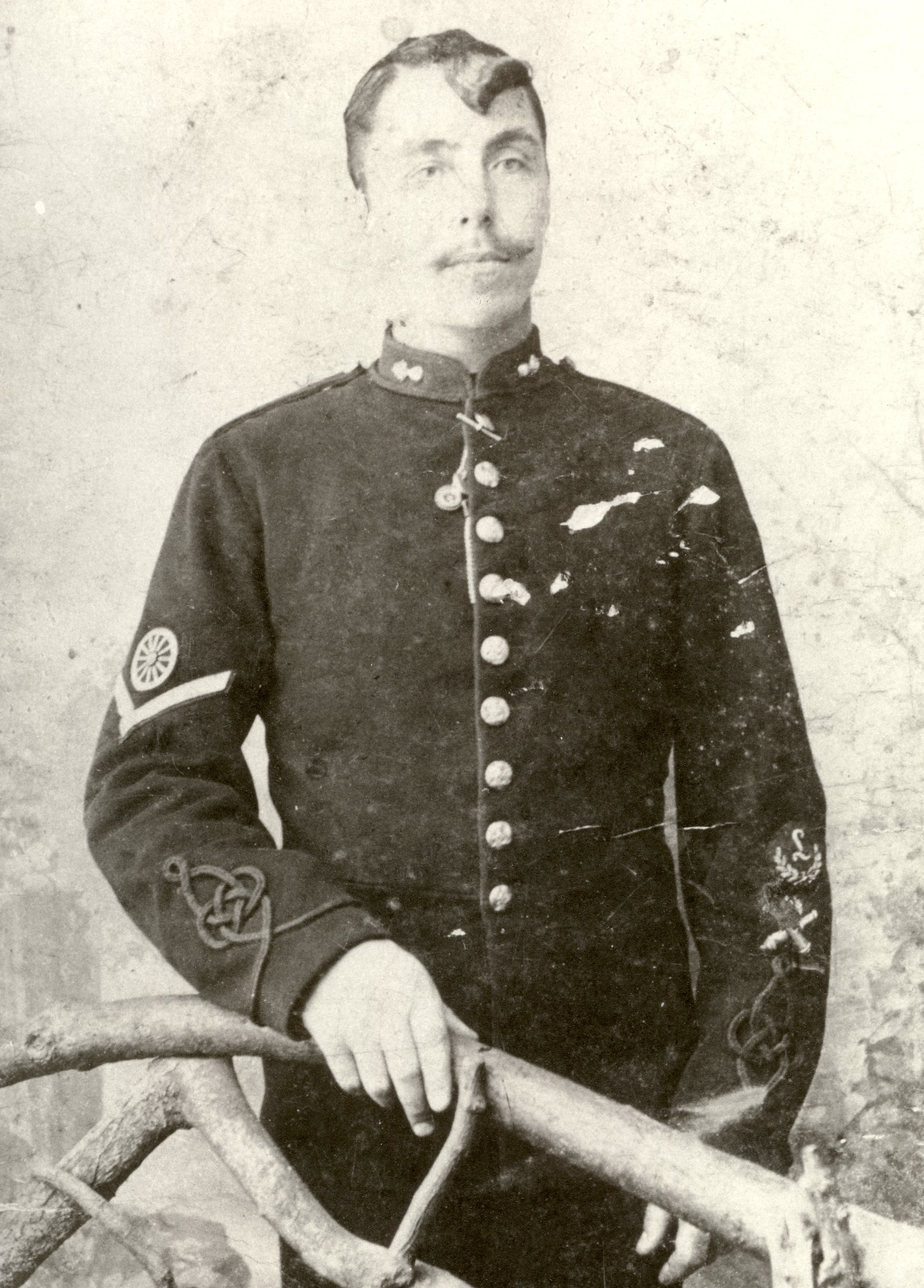

The only existing photograph of George is believed to have been taken around the time of wedding to Louisa in 1895.

George Henry Chambers, probably 1895.

The photograph depicts him in his dress uniform, featuring a blue jacket with a red collar and gold braid trim. On the right arm of the uniform, there is a single golden chevron with red trim, indicating his rank as a bombadier, to which he had recently been promoted. The chevron is located below a gold wheel, which represents his trade as a wheeler in the battery. The left arm of the uniform features a gun layer badge, an ‘L’ in a wreath, which is exclusive to the Royal Artillery. Gun layers were specially trained in the laying of guns, responsible for calculating and setting their vertical alignment.46 Below it is a badge on that showcases his receipt of the first prize for being the most efficient gunner in the unit. Lastly, there is an unidentified clasp present at the neck.

George Henry Chambers, colorised version.

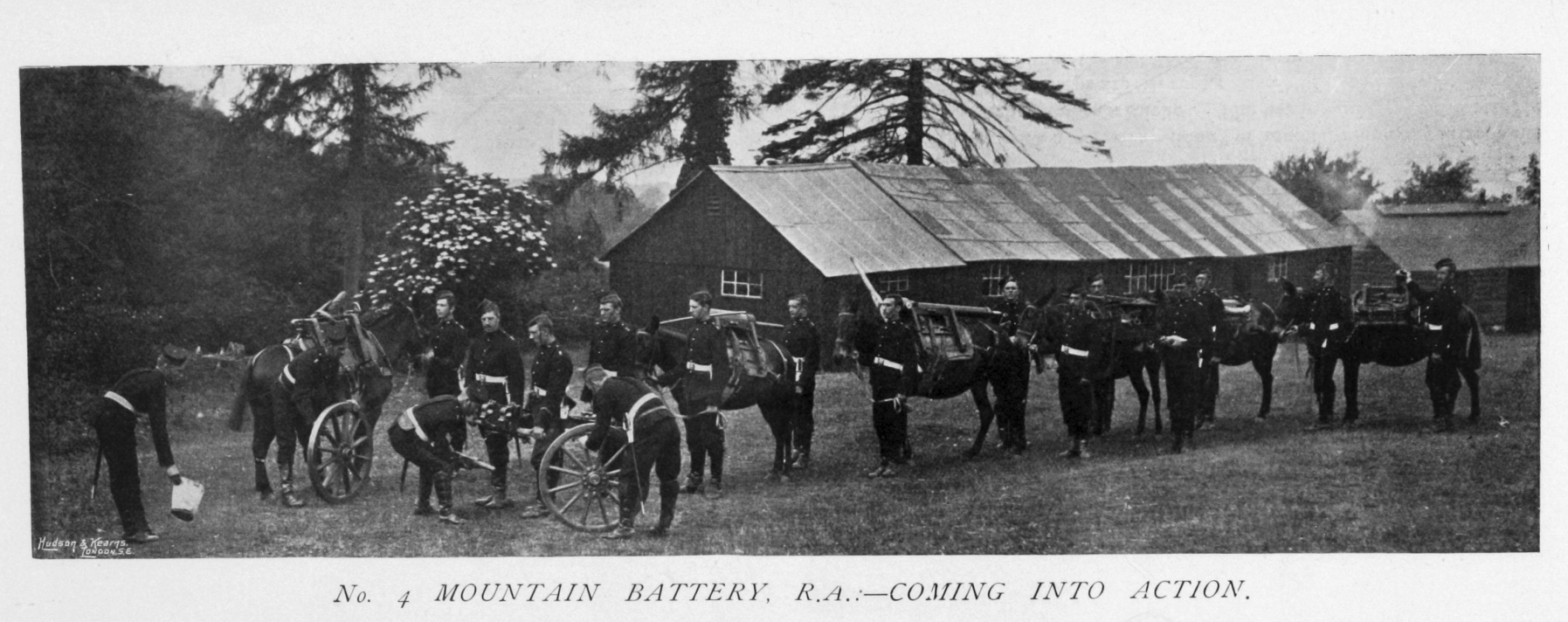

In 1896 the 4th Battery were featured the Navy & Army Illustrated magazine.47 Two photographs show one of the sub-divisions coming into action and these may have been taken at Newport.

No. 4 Mountain Battery R.A - Coming into Action. Navy & Army Illustrated magazine, 1896.

No. 4 Mountain Battery R.A - Coming In Action. Navy & Army Illustrated magazine, 1896.

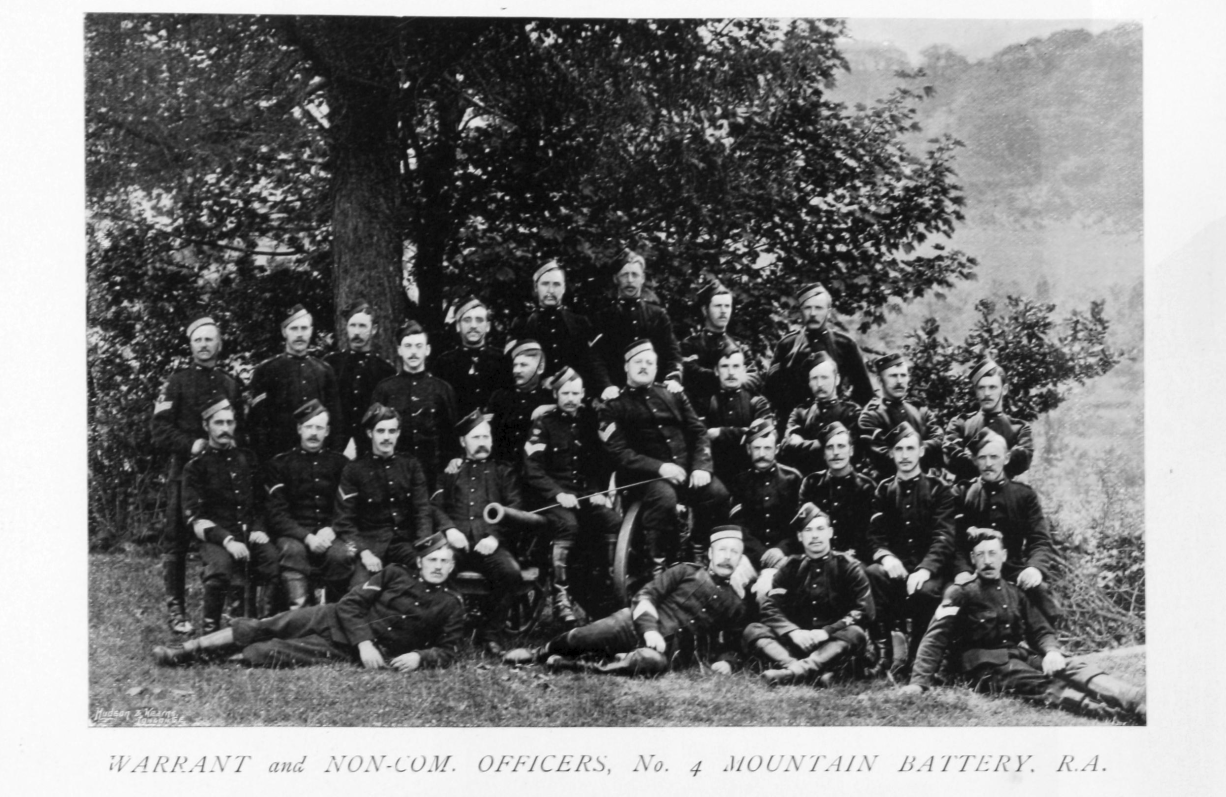

The magazine included a photograph of the warrant and non-commissioned officers at the time. In the centre, seated on a gun is Battery Sergeant-Major Connor. The remaining officers are not named but almost certainly George would have been among them.48

No. 4 Mountain Battery R.A - Warrant and Non-com Officers. Navy & Army Illustrated magazine, 1896.

Occupation of Crete

George and Louisa had been married for just over a year when, on January 2nd, 1897, they welcomed their first child into the world - a baby girl. In memory of George’s mother, the couple named her Rebecca and she was baptized by the regiment’s Roman Catholic chaplain on January 27th.49

Life as a soldier’s wife was not easy. The wife became part of the regiment and was recognised at the rank of her husband but was also subject to army discipline. The wife was expected to maintain their quarters to army specifications and in some regiments, quarters were inspected daily. With a new baby in tow, it would have been especially challenging for Louisa..

Unfortunately, George was to be absent for almost all of Rebecca’s first year. In January of that year, uprisings erupted in Crete as Christian insurgents rebelled against Turkish rule. In response, several countries, including the United Kingdom, sent troops to the island to impose peace. The 4th Mountain Artillery, along with the 1st Suffolk Infantry Regiment, were chosen to support the international effort. They departed from Newport, traveling by train to Southampton, and then by chartered commercial steamer Sumatra. After stopping in Malta, they landed at Candia (Heraklion) on April 29th, leaving George far from home for an extended period of time.50

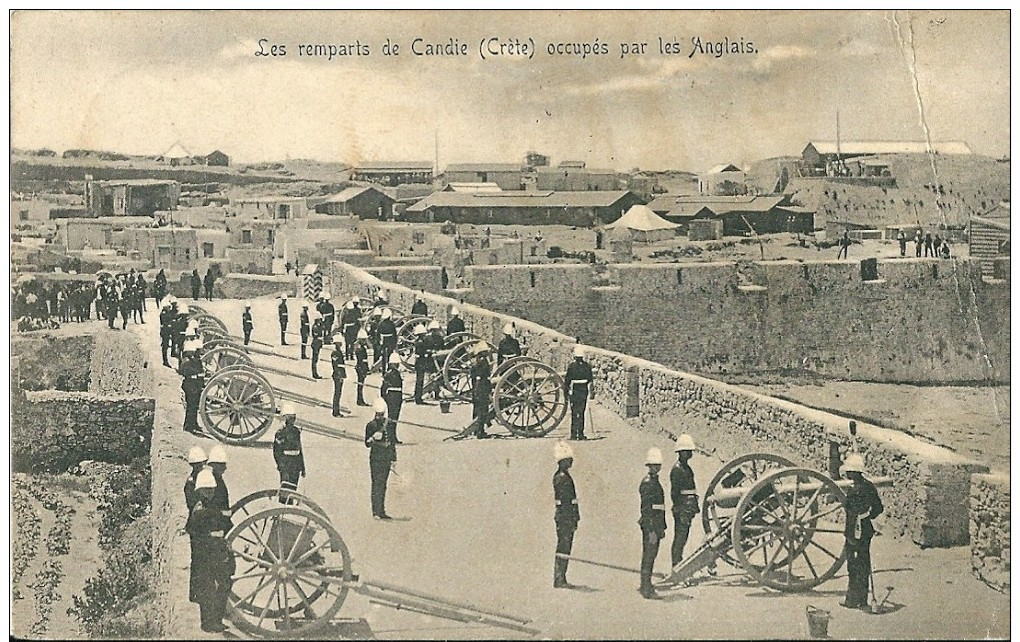

4th Mountain Battery, Candia Ramparts. 1897.

At that point, the conflict in Crete had mostly ended and the regiment was mainly engaged in peacekeeping tasks, manning the guns on the ramparts of Candia.51 However, the guns were never fired during their stay on the island, primarily serving as a visual deterrent. Later that year, they joined with the rest of the Empire in celebrating Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The London Evening Standard reported on the ceremonies:

Yesterday morning a review was held of the International forces by the Admirals, escorted by a Guard of Honour composed of a Turkish band and soldiers, with British Marines. After the inspection the troops marched to the fort and the lines of the fortifications, where the Royal Artillery fired a salute of twenty-one guns, and three cheers were given for the Queen.52

The unit maintained an average strength of 125 men, but disease and infection was rife and they recorded 140 hospital admissions and two fatalities during their time in Crete. Two soldiers were invalided back to England. 53

Louisa’s brother Frank Hemmings was also in Crete at that time.54 The Royal Welsh Fusiliers had arrived from India in March, also via Malta, on the transport ship Malacca.55 They remained until August when they left for Egypt only to return to Crete the following month to help quell riots that had erupted on the island. They then departed in December, bound for China.

George left Crete with the regiment in November 1897 and arrived in back in Malta on the 25th of that month. After spending the winter at Pembroke Camp, they finally departed for Southampton on the transport ship Jelunga on the 13th of February the following year, 1898. His return to England marked the end of a journey that had begun almost a year earlier in Newport. 56

His daughter, Rebecca, was now one year old and later that year, on 20th November, she was joined by a new sister, Eileen. Eileen was baptized two weeks later on 4th December, not by the regimental chaplain, but by Father Butcher of St. Mary’s Church in Newport. Louisa was determined to retain her Catholic upbringing, a tradition that George was later to continue.

South Africa

Early the next year George received a promotion to Corporal Wheeler and on the 10th March 1899, having served his original twelve years, he extended his service to twenty-one years. In January of that year the artillery service had been reorganised into two corps – the Royal Horse and Field Artillery and the Royal Garrison Artillery. The Mountain Artillery found themselves designated as Garrison Artillery which, since most of its personnel were former Horse of Field artillerymen caused considerable discontent. There was to be no movement between branches of the service, but it was decided that Garrison artillerymen could transfer to the Horse or Field Artillery when an opening presented itself.57 George was to take advantage of this exemption the following year.

On 11th October war broke out in South Africa when the Boers invaded and occupied northern parts of the British colony of Natal. By November 2nd, the Boers had besieged the town of Ladysmith, where the British forces had retreated after a series of humiliating defeats. The situation was dire, and reinforcements were urgently needed. On the 14th November, the 4th Mountain Battery were ordered to travel to Natal to replace the 10th Battery, which had been captured with 800 other soldiers at Nicholson’s Nek. The South Wales Daily News wrote of their departure:

On Monday the men of the 4th Mountain Mule Battery, which is ordered for active service in South Africa, paraded in the Barrack-square at Newport for the purpose of being presented by the Mayor (Councillor Greenland) with the £100 worth of comforts which have been subscribed by the town for their use on the voyage. The battery, 280 strong, was in kharki, and under the command of Major Simpson. They looked a fine, serviceable lot of fellows, ready to do and dare anything. They were formed in a hollow square, the fourth side being lined by spectators.58

The paper went on to describe the luxuries that had been procured for the soldiers:

The comforts, which consist of condensed milk, cabin biscuits, cheese, butter, assorted jams, brawn, tinned rabbit and salmon, hams, sugar, ground coffee, pickles, and (at the men’s request) three dozen of Eno’s fruit salts, will be laden on a railway truck, and will accompany the men.59

Eno’s fruit salts were a very popular brand of antacids consisting of sodium bicarbonate, citric acid and fruit flavourings60. The battery travelled by train to Liverpool to board the Narrung cargo ship that would convey them to South Africa. New mules had been procured for the battery but these had shown poor temperament when being loaded in London, echoing the mule stampede that had led to the defeat and capture of the 10th Battery. A sketch writer in the Dublin Daily Nation wrote:

Mules stampeded at Nickolson’s Nek, and the Boers were made happy. By way of making the Boers happy another time mules have been despatched to South Africa, and these we can only describe as extraordinarily “absent-minded beggars.” Indeed “absent-mindedness” seems to be the key-note of the campaign on the British side. The mules just shipped in the Thames are to serve the 4th Mountain Battery of Artillery. But during the process of embarkation the order was reversed. The mules served nobody. On the contrary, they had to be dragged aboard ship or carried thither. One hundred and seventy-six of these martial brutes afforded juvenile Cockneydom more fun in one afternoon than that precocious young animal usually enjoys in three hundred and sixty-five.61

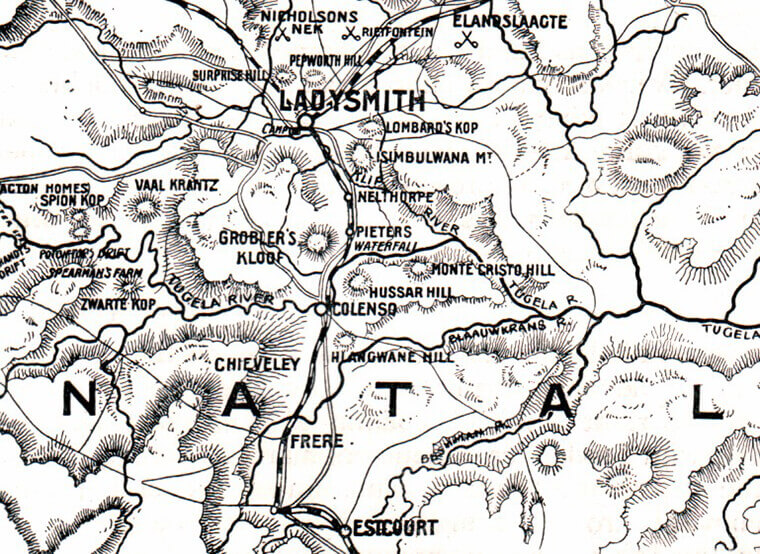

The Narrung arrived in Durban on the 12th December. At that time Durban was the capital of the Colony of Natal, a British colony in south-east Africa. The battery was to form part of the Fifth Division which reinforced General Redver Buller’s forces at Estcourt, 100 miles to the north-west of Durban and 45 miles south of Ladysmith. To the north, separating them from Ladysmith, lay the Tugela River, crossable in only a few locations all of which were well defended by the Boers especially where the railway crossed the river at Colenso. Downstream from Colenso the Tugela entered a steep gorge but upstream, to the west, lay flat ground on the British side of the river and high ground on the northern side, including the steep hill known as Spion Kop. It was here that General Buller decided the advance to Ladysmith should begin.

Map of Natal area, 1899.

General Buller’s forces now numbered over 17,000, including nine batteries of field artillery and several long range Naval guns62. On 10th January Buller gave orders for the main body of the force to march west to attempt the river crossing at Potgieter’s Drift and Trichard’s Drift.

The six guns of the mountain artillery were not considered useful on the battlefield as they were of limited range and still used black powder rather than the smokeless cordite of larger artillery pieces. They remained at Chieveley Camp and spent ten hours the next day shelling Boer positions.63

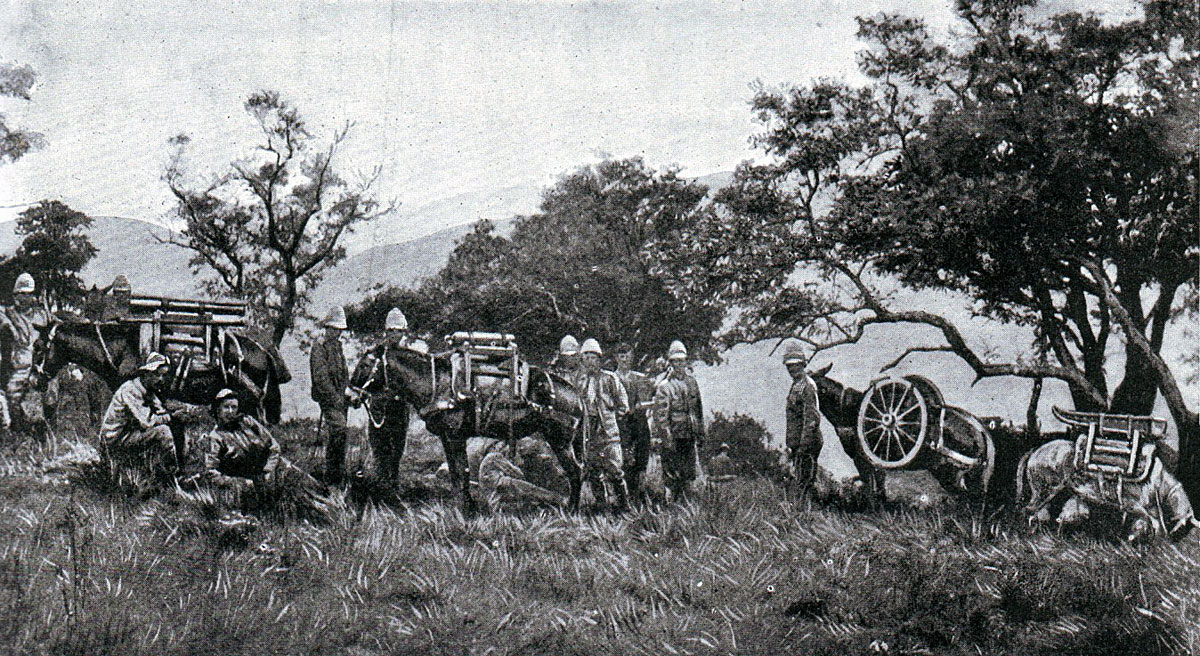

On 23rd January they were commanded to join the main force at Spion Kop that night. The field artillery had determined that it was impossible to get their 15-pounder guns up the slopes to bombard the Boer positions and the smaller guns and sure-footed mules of the mountain artillery were required.

George and the others started from Chieveley by train for Spion Kop that morning but transport delays meant they commenced march from Frere at 5.50 p.m., but did not make much progress in the dark and rain. The men marched all day of the 24th, reaching Trichard’s Drift to the south-west of Spion Kop. General Buller commanded them to rest before proceeding to the hill. They arrived at the foot at 7.30 p.m and the ascent was commenced at 12.30 a.m. However, having already occupied an area close to the summit of the hill the British forces were retreating in disarray, having endured hours of shelling from the Boer positions at the summit. Colonel Thorneycroft, who had assumed command of the troops on Spion Kop upon the death of Major-General Woodgate, had received no signal from General Buller that reinforcements were on their way and, also unaware that the Boers were as good as defeated, had ordered a retreat. The 4th Mountain Battery withdrew with them across the Tugela to regroup. 64

4th Mountain Battery, Spion Kop, South Africa, 1900.

A gunner in George’s battery, J. Stinchcombe, wrote in a letter to his mother of the events that night:

We started our march in the pitch dark. It was all up-hill and we could hear the Boer pom-pom going. It is a horrible sound, and it does a lot of terrible damage to our infantry. It turned out that our destination was Spion Kop, where the big slaughter was. You see they could not hold the position without artillery, and we were the only lot that could climb the hill with guns. That was why they had sent for us. But through not having our transport that seven hours had made us late, as just as we got there the infantry was beginning to retreat. Perhaps had we got up there eight hours earlier, we might have saved Spion Kop. … Of course the battery was disappointed at being late, and as the infantry was staggering down the hill, all they could say was “If you had only been earlier you would have saved some lives.” It was hard on us after marching day and night to get there.65

The battery retired back to camp but just as they were about to sleep they received an order to take up positions on another hill, Spearman’s, south of Potgieter’s Drift close to General Buller’s headquarters. They camped there for a day, while all the other troops retired to new positions south of the river. The 4th Battery were the last to leave with the Boers advancing quickly towards them, shells landing a mere fifty yards behind as they started off.66

4th Mountain Battery, in action on Schwartz Kop, South Africa, 1900.

This second attempt to cross the Tugela and relieve Ladysmith had been another disaster. The news of the defeat at Spion Kop caused a crisis in Britain and nearly brought down the government. General Buller’s reputation was destroyed by his mistakes and he was to be dismissed from the Army at the end of the war.67

George and the 4th Mountain Battery were involved for Buller’s third attempt to cross the river at the Battle of Val Krantz on the 5th February. Almost immediately after the defeat at Spion Kop, General Buller had commenced preparations for a crossing at Munger’s Drift to the east. The plan included the construction of one and half miles of road up Schwartz Kop, a precipitous hill, that would allow the placement of artillery to support the assault. The road took six days to complete and the six screw guns of George’s battery were hauled to the summit along with six naval 12-pounders and two field artillery 15-pounders. The weather was too bad to allow more artillery to be transported up the hill.68

Throughout the day on 5th February they shelled the ridges occupied by the enemy to cover the advance of the British infantry.69 They were forced to retreat when the quantities of smoke from the 4th Battery’s black powder cannons gave away their position attracting enemy fire.70

This attempt to break through the Boers defences ultimately ended in failure for the British once again when the infantry troops came under fire from heavy artillery brought up by the Boers overnight.

On 12th February, General Buller ordered a fourth attempt to relieve Ladysmith by taking the strategically important Pieter’s Hill. British infantry advanced into Colenso and secured positions up to the rail bridge over the Tugela. On the 26th all bar one of the artillery batteries took up positions along the river gorge to the east, a total of seventy guns. They were supported by the long range guns at Chieveley. Four guns of the 4th Mountain Battery were placed to the east of the field artillery on the Hlangwane ridge and the remaining two guns were hauled high up on the northern slopes of the Monte Cristo.71 George could have been stationed with either one.

The operation commenced by a slow and occasional firing of the artillery, as three infantry brigades cautiously advanced to positions in the river bed. Finally, when all elements were in position, the massed artillery began a heavy bombardment of lyddite and shrapnel. As the infantry advanced on the hill from three directions the artillery increased its rate of fire, until the last moment before the final assault began. At that moment the artillery ceased firing and the infantry easy stormed the positions and took control of the hill. The Boers defences crumbled and the British marched onward, arriving in Ladysmith the next day.

Harold Wallbank, a gunner in the 4th Mountain Battery wrote a description of the events in a letter to his parents:

About 8 a.m. that day the artillery commenced shelling the position. We were in action where we could get a good view. About 1 o’clock the infantry, who had been under cover, commenced their dangerous ascent up three hills at once this time. I only watched them on the centre one, and it was a lovely sight to see the brave fellows. They would run ten or twenty yards and then drop flat, and in a few minutes be up again and down again. But all the while the Boers were pouring a continuous rifle fire into them. Every now and then you would see some poor fellow drop and remain – a speck of brown – on the green grass. As they got near the trenches they gave such a cheer and dashed at them with fixed bayonets. The Boers, however, did not wait for that; they don’t like our steel, and they ran bodily from the trenches, but our artillery was waiting for that, for they got such a storm of shrapnel, that very few of them got away.72

He went on to write of the battery’s next movements:

Our Battery did not have the pleasure of entering Ladysmith. We remained on the hill a couple of days, almost smothered by the stench of dead horses and Boers, incompletely buried. We have been sent back to Chievely, along with the garrison and Navy. It seems to be a general idea that we have finished up at the front with this battery, owing to the smoky powder and the short range of the guns.

George received the Tugela Heights clasp, which was awarded in combination with the Relief of Ladysmith clasp, number 251. Both were honours awarded to regiments that took part in the battles at Tugela between 14th and 27th February, in which Britain had sustained over seven thousand casualties. The clasps would have been attached to the Queen’s South Africa Medal which he received for his service in South Africa. The whereabouts of this medal is unknown but it was in the possession of his son William along with George’s

Queen’s South Africa Medal with Tugela Heights and Relief of Ladysmith clasps.

long service medal until the early 1960s when William passed them to his brother George.73

The battery returned to Estcourt where George remained for several months until, on 16th May 1900 he was posted back to the Mountain Artillery depot at Newport.74 He returned to England on the 16th June. The rest of the 4th Mountain Battery remained in South Africa.

Three months later, on the 1st September, he was transferred to the 109th Field Artillery Battery. Twenty-one new batteries had been created at the beginning of the year and the 109th was one of three formed at the Artillery service headquarters at Woolwich, London. With his tour of India and two active service campaigns under his belt, George would have been one of the most experienced artillerymen in the new battery, which would have mainly comprised new draft soldiers. Together with Louisa and their two young daughters, Rebecca, then three and Eileen, nearly two, they moved to the prestigious and historic Woolwich barracks. This would have been a significant step up in conditions for George and his family as they were to be quartered in Cambridge Cottages, eight two-storey buildings constructed as “model lodgings” for married artillerymen in the 1860s.

In the new year, Queen Victoria died, ending a 63 year reign during which the British Empire had grown to touch every part of the world. George’s battery travelled to St. James’ Park to deliver the eighty-one minute guns on Horse Guard’s Parade. They quartered at St. John’s Wood barracks and delivered a forty-one gun salute the next day to the new King before returning to Woolwich barracks.75

In a conversation in 1986, George’s son William recalled that his father had told him that he had been in charge of the gun-carriage that carried Queen Victoria’s coffin at her funeral.76 While there is no concrete evidence that this was the case, three different gun carriages were used to carry the Queen’s body, one at Cowes to convey her to the station, one in London for the public procession through the streets from Victoria to Paddington Stations and the last at Windsor that would take her from the station to St. George’s Chapel.77 The carriage used in London had been freshly constructed in the Royal Carriage Department at Woolwich Arsenal and formed part of equipment destined for the new field batteries that had been formed78 so it is plausible that this was or became the carriage George was in charge of. The carriages at Cowes and Windsor were driven by artillerymen, although at Windsor the carriage broke under the weight of the coffin, loosening it from the horses. Nearby naval detachment seized hold and pulled it to its destination.79

George and Louisa were recorded in the 1901 census at Cambridge Cottages at the end of March80. George was thirty-four years old but gave his age as thirty, while Louisa’s age was listed as twenty-six instead of twenty-five. The gap in ages was perhaps still a sensitive topic for them to reveal.

At the time of the census, Louisa was heavily pregnant with their third child and five days later, on the 5 April 1901 she gave birth to Hilda.

George’s sister Helen, known as Ellen, was also living in London at that time. After the deaths of their parents she had worked as a servant in Suffolk and Norfolk before moving to London and eventually marrying Henry Pickett in 1894. He was a soldier in the Royal Fusiliers who had been discharged in 1897 after completing his twelve years service but, at the outbreak of war, had been recalled and posted to South Africa in 1900.

Ellen and Henry lived in Horsleydown, a small parish south of the river opposite the Tower of London.81 They had three children Harry, Ellen and Florence who were of a similar age to Rebecca and Eileen. George and Louisa would almost certainly have visited Ellen while they lived in London. The families remained in contact for many years after – George’s son, William, continued to visit into the 1920’s even though, at the time, he was living three hundred miles away in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.82

The war in South Africa had concluded and military life was quieter than it had been for some time. with time for cricket and football matches between batteries. The batteries would convene for annual gunnery practice either on Dartmoor or Salisbury plain involving a march through southern England, billeting at towns along the way where they would invariably be fêted by the locals.

George and Louisa were to remain in London for another year when, in June 1902, the 109th Battery was relocated to Brighton in Sussex, and it was there that George received a promotion to his highest rank as a sergeant wheeler. .

The following year, on 29th March, 1903, their first son was born in Preston Barracks and they named him George Henry, after his father.

During the summer of 1903, after the annual gunnery practice, George was transferred to the 37th Battery of Field Artillery, a howitzer battery equipped with small 5-inch guns designed to bombard enemy position. They were stationed in Woolwich for a brief period before being posted to Newbridge in Ireland in August 1904. A year later, on 26 August, 1905, Louisa gave birth to their second son, William Joseph, named for each of George and Louisa’s fathers. He was baptised on the 1st October.83

In June 1905, George’s former unit, the 4th Mountain Battery was disbanded, and its personnel were reassigned to other mountain batteries. It had returned to Monmouthshire after spending several years in Egypt but the short ranged, black powder guns had shown their limitations in South Africa and were deemed obsolete. The 10th had been converted into a siege train battery on it’s return from Pretoria in 1903.

After two more years in Ireland, George and Louisa welcomed their fourth daughter, Louisa Alexandra, on July 10th, 1907. She was baptized as a Roman Catholic by Father Murray in Newbridge on August 4th of the same year.84 The following month, George was posted to his final station in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a city he was to make his home for the remainder of his life.

Civilian Life

On 22nd December 1908 George was discharged after twenty-one years of service in the Royal Artillery. In all he had spent three years in India and been deployed on active service twice, in Crete and South Africa.

He was awarded the Army Long Service and Good Conduct Medal, a gratuity of £5 and a pension of twenty-one pence per day for life.85 George’s conduct was deemed exemplary, without offences or instances of drunkenness. His commanding officer, Lieutenant Conner, confirmed this in a written reference:

R.A. Barracks

Newcastle

30 Nov 08

Sergeant Chambers has served under me for the last three and a half years.

He is honest, sober, industrious and capable.

D G Conner

Lieut. R.F.A.86

George was now forty-one and now needed to adjust to a life outside the army in an unfamiliar city. Louisa, thirty-two, was six months pregnant with their seventh child.

They initially lived at 61 Darnell Street, just a few hundred yards from the Artillery Barracks.

Aerial photograph looking east taken in 1931 showing Darnell Street, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. To the upper left are the artillery barracks. The building in the centre is Todds Nook school (closed 1983). Darnell street runs from left to right just in front of the school. The lake to the upper right is now called Leazes Park Lake.

Helen Mary (later known as “Nel”) was born on 29 March 1909 at Darnell Street. George gave his occupation as wheelwright on his daughter’s birth certificate, but it is unclear if he was employed as such or simply stating his trade.87

By the time of the census taken in April 1911 the family were living at 8 Joseph Street in Elswick.88 This was just a short walk from the Armstrong and Whitworth factory where George now worked as a caretaker in one of the laboratories. The Elswick Works was vast, consisting of over 160 specialized workshops extending for over a mile along the north bank of the Tyne. The factory turned out around 6,500 tons of guns, torpedo tubes, artillery and mountings per year.89 As well as armaments, the factory built merchant vessels and warships, although by this time the dockyards were deemed too small to accommodate modern ships and the company had begun to move construction to a new site east of the Tyne bridges.

Map of area around Joseph Street, Elswick from OS 25 inch map series 1892-1914.

Joseph Street was situated to the south of St. John’s Cemetery, just to the west of the junction between St. John’s Road and Gluehouse Lane, but all of this area, including St. Aidan’s Church has since been demolished.90

Their older children, Rebecca, Eileen, Hilda, George and William were attending the school attached to St. Michaels Roman Catholic Church opposite Elswick Park, about a quarter of a mile to the east.91 William was later to marry Florence Hall at this church in 1935.

In the census both George and Louisa at last gave their full ages of forty-three and thirty-five. Later that year Louisa gave birth to a son who they name Francis Patrick. He was born on 18th October, 1911 and was to be the last of their children.

Death of Louisa

Two years later, on the 3rd November, 1913 Louisa died unexpectedly during childbirth at their home in Joseph Street. She suffered complications due to placenta previa where the placenta blocks the opening to the cervix. During childbirth the abnormal position of the placenta causes blood vessels to rupture and she would have bled heavily, ultimately dying through heart failure. This condition may have caused her to bleed during the late stage of pregnancy too.

She was buried on 7th November in St. John’s cemetery, a multi-denominational burial ground just to the north of Joseph Street.92 Her funeral was attended by her elder brother Frank Hemmings and sister Harriet, then Harriet Gammon. Seeing that George was now responsible for eight children, four of whom were under 10 years old, they offered to take Rebecca back with them to live in South Wales.93 In the event, Rebecca, who was nearly seventeen, remained with the family and took over household responsibilities with Eileen, who between them would have cared for the younger children while George worked.

Later Years and Death

After Louisa’s death, George made sure that the children followed their mother’s Catholic upbringing, including attending church every Sunday and remaining at the Catholic school at St. Michael’s.94

In autumn 1916, Rebecca married William Bell, a porter on the Northumberland Railway and the following year George became a grandfather with the birth of their daughter Mary.

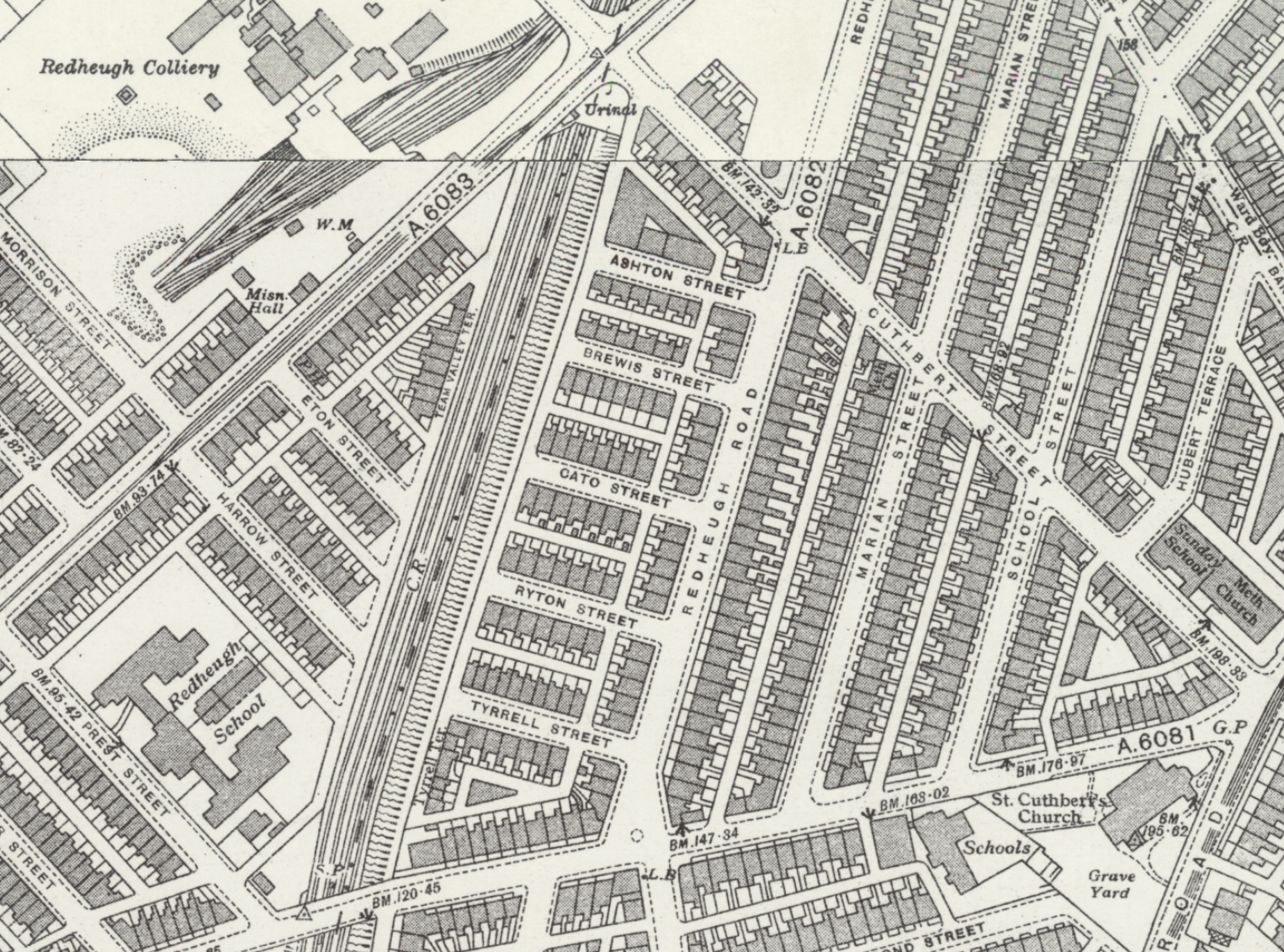

Map of area around Cato Street, Gateshead from OS 25 inch map series 1892-1914.

Some time before 1921 George moved his family to 26 Cato Street in Gateshead, south of the river. Gateshead had grown over the previous hundred years from a small riverside trading town to a sprawling industrial borough. The poorest areas were to the north around the town’s historic centre along the banks of the Tyne and along the High Street. Bensham, to the south, had sprung up originally as a wealthier suburb but was now dominated by streets of well-spaced, low to middle quality working class housing.

Cato Street was a short street that ran from Redheugh Road in the east to the railway embankment in the west, in an area to the north-west of Bensham.95 Many of the men living in this area worked the nearby Redheugh Colliery to the north-west a major employer in the area until 1927 when it was abandoned. As was typical in this area, the houses were terraced and divided into two floors of living space, in a style known as Tyneside flats. These were intended to be of good quality and to house no more than two families, on different floors but each with their own front and rear entrances. Each flat typically consisted of a heated parlour, bedroom and kitchen with a scullery and pantry and were provided with either an ash or a water closet and a coal house in its part of the yard.

George applied for his children to attend the nearby Catholic School but no places were available. The Church of England school would not admit them on the grounds that they were Catholic so they had to apply the board schools run by the state. The boys George, William and Francis attended Redheugh Boys School in nearby Prest Street and the girls Louisa and Helen were sent to the separate girls school.96

In February 1919, Rebecca gave birth to George’s second grandchild, Jean, followed by a third, William, in 1921

The 1921 census shows a change in circumstances for George, where he was still shown as a caretaker for Armstrong Whitworth but was now out of work. It had become harder for the family to make ends meet but they made the most of what little they had. George’s daughter Nel recalled that they used to have all-night parties at Cato Street, but without alcohol, which they couldn’t afford.97 Her father didn’t drink alcohol at all.

Eileen, aged twenty-two, was now managing the household duties while Hilda, twenty, had found work as a grocer’s assistant in a shop on Coatsworth Road98, the main thoroughfare through Bensham. George was a wagon man, delivering bottled drinks for Joseph Wilkinson, a manufacturer based off of nearby Cuthbert Street. William, aged fifteen, had left school and was working as a porter for Julius Isaacs, a pawnbroker on High Street, about a mile away. The three younger children, Louisa, Helen and Francis were still attending school.

Some time after, the younger George followed in his father’s footsteps by enlisting in the 19th Regiment of Foot, the Green Howards.

On 16th November, 1923, Eileen married Joseph Burke, an engine fitter, at St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic church in West Street, Gateshead.99 The register records George’s occupation as a school caretaker so it seems he must have found new work after leaving Armstrong Whitworth. Eileen had still been living at Cato Street but she now left to live with her new husband across the Tyne in Heaton, leaving Hilda to look after the household.

Just a few weeks after seeing his second daughter marry, George died.

He had been suffering from a bout of bronchitis, a persistent problem he had lived with since his time in India. His son, William, recalled the events of that night:

I had sat in with father in the evenings, talking and attending to his needs during this illness. One evening I decided to go out with a mate for a walk. After some time I felt a definite desire to go back home. On the way back I was met by my brother George who was at home on leave from the army. George and I parted company from my mate and walked on together, then George turned to me and said, “Did you know your father is dead?” It was the first evening I’d had been away from my father.100

George died on the 9th December, 1923101. He was fifty-five years old. It seems that his family knew how ill he was and were with him at Cato Street. Eileen was the informant recorded on his death certificate and was present at the time of his death. The attending doctor decided that the cause was his bronchitis and a dilated heart.

He was buried three days later in the same grave as Louisa in St. John’s cemetery in Elswick.

George and Louisa’s Children

The family kept the house at Cato Street after their father’s death and probably remained there for the remainder of the 1920s which were difficult times in the industrial north. The return to the gold standard had made coal and steel exports uncompetitive and employers were squeezing worker’s wages tightly.

Work was hard to find, and low paying, so the remaining family probably stayed together through economic necessity. Besides Rebecca and Eileen who were already married and George, who was travelling with the army, the other siblings remained unmarried for over a decade.

Louisa, Helen, Eileen and Hilda on Louisa’s wedding day 9th Nov 1935

William, who was only partially sighted102, found later employment as a labourer and married Florence Hall in 1935 at St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Church in Elswick. A few years later they moved to the east end of London.

Hilda married Cyril Quincy in 1936. He was the manager of a pawnbroker in Doncaster and they lived there after they married. Hilda died a few years later, in 1942.

In the time after her father’s death, Nel worked as a shop assistant and as a domestic servant. Eventually, she ended up looking after her sister Eileen’s children Diane, Joseph and Edmund Burke.103 She married Ernest Pringle in 1937 before moving to north London in her later years.

Frank, who was just twelve when his father died, trained as a baker and later married Kathleen Nichols in 1937 in Clacton, Essex.

George was posted to the West Indies, Egypt and Shanghai before ending up in India and marrying Maud Mcleod, a Scottish nurse working in India. He reached the rank of sergeant in the Green Howards and returned to England at the outbreak of the war in 1939 to train recruits at Caterham.104

Both Rebecca and Eileen remained in Newcastle with their families

-

John Marius Wilson’s Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales ↩︎

-

1851 England Census; Class: HO107; Piece: 1796; Folio: 206; Page: 6; GSU roll: 207445 ↩︎

-

1861 England Census; Class: RG9; Piece: 1152; Folio: 27; Page 12 ↩︎

-

In a foreshadowing of Rebecca’s own untimely death the death of George Brooks scattered his family widely. His daughter Anna Maria ended up in Middlesborough and the youngest, Betsy, ended up in Durham. ↩︎

-

Birth certificate of William George Chambers, 1865 ↩︎

-

The East Anglian Daily Times, Saturday September 6 1879. ↩︎

-

England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915, entry for William Chambers, Hoxne, Suffolk, 1879, Jul Qtr, Vol 4a, Page 332. ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

Death certificate of Rebecca Chambers, 1881 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

Conversation with Jane Ann Horny nee Chambers, 4 July 1989 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1989 ↩︎

-

Robert Chambers, 1891 England Census. Class: RG12; Piece: 1459; Folio: 150; Page: 3; GSU roll: 6096569 ↩︎

-

William Chambers, 1891 England Census. Class: RG12; Piece: 1458; Folio: 175; Page: 6; GSU roll: 6096568 ↩︎

-

James Chambers, 1891 England Census. Class: RG12; Piece: 1458; Folio: 175; Page: 6; GSU roll: 6096568 ↩︎

-

John Chambers, 1891 England Census. Class: Class: RG12; Piece: 3954; Folio: 43; Page: 17; GSU roll: 6099064 ↩︎

-

Ellen Chambers, 1891 England Census. Class: RG12; Piece: 1544; Folio: 82; Page: 8; GSU roll: 6096654 ↩︎

-

England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915, entry for Ellen Chambers, Pancras, London, 1894, Jan Qtr, Vol 1b, Page 32. ↩︎

-

Helen may have lodged in London with Eliza, the widow of her uncle George who had moved there between 1851 and 1858. It’s possible that they took her in or even adopted her after the death of William and she may then have regarded George as her father. ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

It’s likely that George took the train to Ipswich. Framlingham was the terminus of the G.E.R Framlingham Branch line that joined the East Suffolk Line between Great Yarmouth and Ipswich ↩︎

-

Short Service Attestation; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

Military History Sheet; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

Ordnance BL 12-pounder 7 cwt; Wikipedia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordnance_BL_12-pounder_7_cwt ↩︎

-

Colonies and India - Wednesday 22 August 1888 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002964/18880822/151/0030 ↩︎

-

Dublin Daily Express - Friday 28 September 1888 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001384/18880928/130/0008 ↩︎

-

Evening Star - Wednesday 26 September 1888 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001707/18880926/035/0004 ↩︎

-

HMS Malabar (1866); Wikipedia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Malabar_(1866) ↩︎

-

Dublin Daily Express - Friday 28 September 1888 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001384/18880928/130/0008 ↩︎

-

Times of India - Thursday 25 October 1888 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002850/18881025/089/0005 ↩︎

-

Deolali transit camp; Wikipedia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deolali_transit_camp ↩︎

-

Deolali camp is the setting for the 1970s BBC comedy series It Ain’t Half Hot Mum. ↩︎

-

Army and Navy Gazette - Saturday 10 August 1889 https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001394/18890810/155/0019 ↩︎

-

Army and Navy Gazette - Saturday 29 June 1889 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001394/18890629/021/0008 ↩︎

-

Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) - Tuesday 24 September 1889; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003221/18890924/215/0009 ↩︎

-

Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore) - Friday 11 October 1889 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003221/18891011/048/0004 ↩︎

-

Englishman’s Overland Mail - Tuesday 17 December 1889 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002921/18891217/011/0004 ↩︎

-

Army and Navy Gazette - Saturday 05 April 1890 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001394/18900405/134/0020 ↩︎

-

Military History Sheet; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

Army and Navy Gazette - Saturday 05 December 1891 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001394/18911205/035/0009 ↩︎

-

Kildare Observer and Eastern Counties Advertiser - Saturday 19 August 1893 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001870/18930819/073/0007 ↩︎

-

Army and Navy Gazette - Saturday 09 September 1893 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001394/18930909/022/0006 ↩︎

-

Various accounts have placed Joseph’s origin in Mexico, Portugal or South America. DNA analysis suggests he had some degree of Indigenous American heritage and DNA matches on ancestry.com may hint towards Puerto Rican connections too ↩︎

-

1891 Census; Class: RG12; Piece: 4368; Folio: 50; Page: 12; GSU roll: 6099478 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

South Wales Weekly Argus and Monmouthshire Advertiser - Saturday 03 February 1894; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003433/18940203/292/0010 ↩︎

-

Laying and Orienting the Guns; https://nigelef.tripod.com/fc_laying.htm ↩︎

-

Navy and Army Illustrated; 18 Sep 1896; Pages 134 and 140 ↩︎

-

The man sitting third from the right, on the second row may be George. His sleeve appears to show the 1st prize gunner award that George wears in his wedding photograph. Alternatively he may be standing fourth from the right in the third row. The man in that position has the distinctive point of hair that George also wore. ↩︎

-

Army Form A. 22.; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

St James’s Gazette - Friday 30 April 1897 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001485/18970430/052/0009 ↩︎

-

https://britishinterventionincrete.wordpress.com/category/european-intervention-crete/british-army-in-crete/royal-artillery/ ↩︎

-

London Evening Standard - Thursday 24 June 1897; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000183/18970624/016/0005 ↩︎

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20221122080349/ttps://www.maltaramc.com/regmltgar/royalart.html ↩︎

-

Military History Sheet; Francis Hemmings 4281; WO97/5095/044; National Archives ↩︎

-

The Royal Welsh Fusiliers arrive. 8 April 1897; https://britishinterventionincrete.wordpress.com/category/european-intervention-crete/british-army-in-crete/royal-welsh-fusiliers/ ↩︎

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20221122080349/ttps://www.maltaramc.com/regmltgar/royalart.html ↩︎

-

The Royal Regiment of Artillery in the Boer War; Joel Dallas Boyd; Oklahoma State University; 1964 ↩︎

-

South Wales Daily News - Tuesday 14 November 1899; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000919/18991114/091/0005 ↩︎

-

South Wales Daily News - Tuesday 14 November 1899; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000919/18991114/091/0005 ↩︎

-

They are still available today, but are mainly sold in India. ↩︎

-

Dublin Daily Nation - Saturday 18 November 1899; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001490/18991118/075/0005 ↩︎

-

Lancashire Evening Post - Thursday 18 January 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000711/19000118/070/0002 ↩︎

-

Letter from J. Stinchcombe; Star of Gwent - Friday 30 March 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003169/19000330/048/0003 ↩︎

-

Minutes of evidence taken before the Royal Commission on the War in South Africa; 1903; https://archive.org/details/b32177367_0002/page/651/mode/1up ↩︎

-

Letter from J. Stinchcombe; Star of Gwent - Friday 30 March 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003169/19000330/048/0003 ↩︎

-

Letter from J. Stinchcombe; Star of Gwent - Friday 30 March 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003169/19000330/048/0003 ↩︎

-

Battle of Spion Kop; https://www.britishbattles.com/great-boer-war/battle-of-spion-kop/ ↩︎

-

Buller’s campaign with the Natal field force of 1900; 1902; https://archive.org/details/bullerscampaign00knoxgoog/page/n138/mode/1up? ↩︎

-

Dublin Daily Nation - Saturday 10 February 1900 ; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001490/19000210/073/0005 ↩︎

-

Letter from Gunner Sale of Shefford; Bedfordshire Times and Independent - Friday 30 March 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000749/19000330/179/0008 ↩︎

-

Buller’s campaign with the Natal field force of 1900; 1902; Chapter VII; https://archive.org/details/bullerscampaign00knoxgoog/page/n138/mode/1up? ↩︎

-

Letter from Harold Wallbank; Lichfield Mercury - Friday 11 May 1900; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000379/19000511/010/0003 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

Statement of Services; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

Morning Post - Thursday 24 January 1901; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/19010124/080/0005 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

Heywood Advertiser - Friday 01 February 1901; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002441/19010201/167/0007 ↩︎

-

Coventry Herald - Friday 01 February 1901; https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000385/19010201/146/0007 ↩︎

-

Letter from Cecil B. Levita; The Times; 1936; http://www.memorialsinportsmouth.co.uk/others/excellent/field-gun-carriage.htm ↩︎

-

1901 England Census; Class: RG13; Piece: 569; Folio: 17; Page: 28. ↩︎

-

1901 England Census; Class: RG13; Piece: 387; Folio: 25; Page: 42 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 18 October 1986 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1986-7 ↩︎

-

Army Form A. 22.; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives; the date of birth on this form is given incorrectly as 25 Sep 1905 and the name of the baptising chaplain is Thomas Lynan. It’s not possible to determine his denomination, but we can assume he was Roman Catholic. ↩︎

-

Army Form A. 22.; George Henry Chambers; WO97/4511/23; National Archives ↩︎

-

£5 was equivalent to about £770 in 2023, 21 pence per day is roughly £14 per day, or £98 per week. The basic state pension for a man retiring at 67 in 2023 is £185 per week. ↩︎

-

Original kept by William Chambers and recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1970 ↩︎

-

Birth certificate of Helen Mary Chambers, 1909 ↩︎

-

1911 England Census. Class: RG14; Piece: 30594. ↩︎

-

Elswick Works, Newcastle Part 2 (1882 – 1928) Part 2 (1882 – 1928); https://www.baesystems.com/en/heritage/elswick-works----newcastle-part-2 ↩︎

-

Present day Amelia Close follows the line of Joseph Street from St. John’s Road to the north and roads called West View and Goldfinch Close now occupy the line of Gluehouse Lane (where William and Florence Chambers lived in 1938) ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 30 July 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

St. John’s Cemetery Burial Register; Reference Number 45366, Folio 147: Louisa Chambers, buried 7; November 1913. She was 38. Grave number “W” UNCON 81. ↩︎

-

Conversation with Helen Mary Chambers (“Nel”), 26 September 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 30 July 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

This part of Gateshead was demolished as part of regeneration in the 1960s. Present day Marian Court occupies this location. The route of the railway line is unchanged. Cuthbert Street to the northeast and Askew Road W to the northwest still exist. Cato street lies at lat 54.95634, long -1.61776 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 30 July 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

Conversation with Helen “Nel” Pringle nee Chambers, 26 September 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

1921 England Census; Class: RG15l Piece: 25133; Schedule 104 ↩︎

-

England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005. General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 10a; Page: 1777. ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 30 July 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007. General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 10a; Page: 852. ↩︎

-

He always had poor eyesight but lost he best eye in an accident where something flew into it, possibly in a mine. This may even have been Redheugh Colliery. ↩︎

-

Conversation with Helen “Nel” Pringle nee Chambers, 26 September 1987 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1987 ↩︎

-

Conversation with William Joseph Chambers, 3 May 1988 as recorded by Jeffrey Chambers in Genealogical Diary 1988 ↩︎